Learning to love a saltmarsh

Saltmarshes are overlooked and under-loved. Their treeless, muddy flats are often strewn with rubbish and garden clippings, they're the haunt of wild pigs and stray cattle, they're dug up, drained, cleared, and burned. They're the sort of place most of us drive past without noticing.

Yet these wastelands are crucial for coastal life, creating fish nurseries, protecting coastlines from floods, and storing carbon. They're also, on closer inspection, captivating.

It's the last day of our fieldwork and we're following overgrown wheel ruts towards the Wapentake Creek saltmarshes on the southern outskirts of Gladstone. We pass garbage bags and a dumped mattress in the bush.

As we get closer, I'm surprised to notice marine plants poking out of the grass. I grew up in western New South Wales, and until now, it just looked like were heading towards an eroded plain like the grasslands I'm familiar with. At my feet are fleshy, segmented, succulent green and red plants – but there's no sea within view.

Jock calls one type a 'jellybean plant', or beaded samphire. Its red pigment is like sunscreen, protecting the plant from full sun.

The saltmarsh itself is fairly dry and covered with algal mat – like it's paved with a mosaic of thick door mats curled up at the edges. Jock tells us the term to describe this pattern is 'tessellated.' If you lift them you might find snails or crabs.

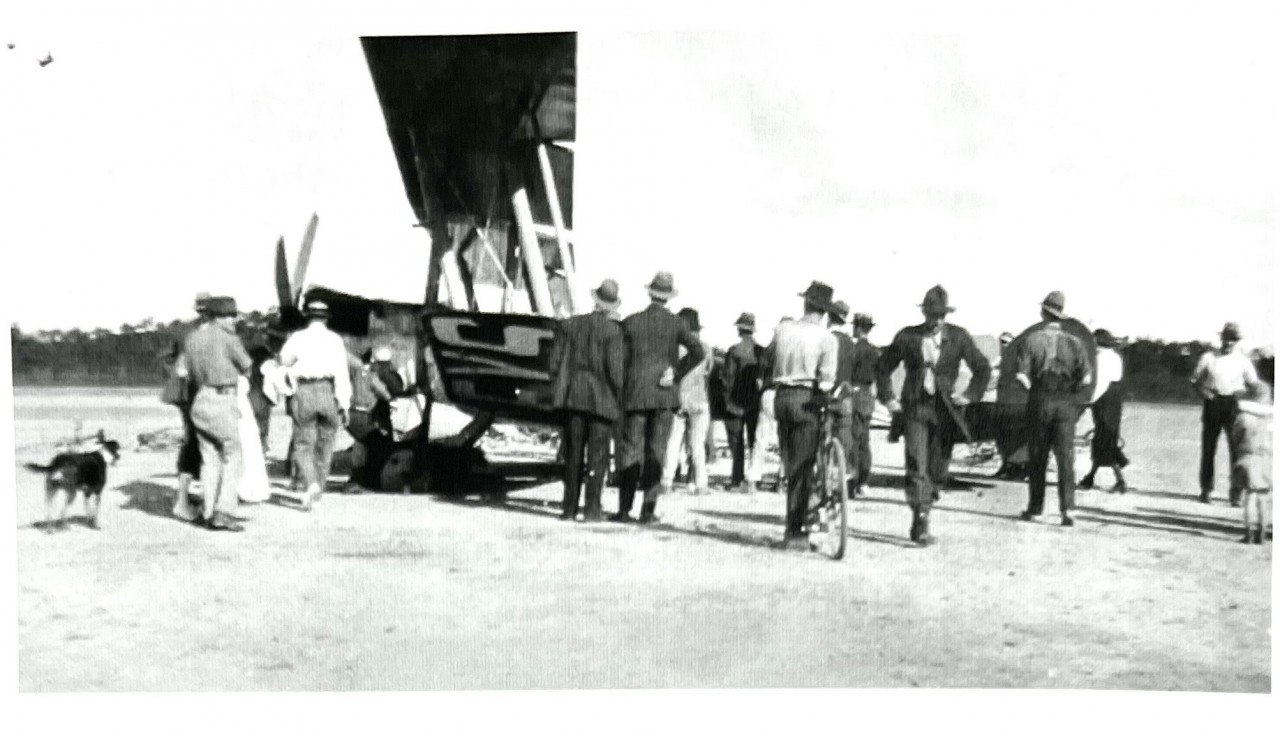

In the early twentieth century, townsfolk here landed planes, raced bicycles and motorbikes, and lit bonfires on the saltmarshes. The port, industry and housing developments destroyed and built over many of the saltmarshes. First Nations people express their dismay at losing the places where they caught fish and crabs and other important foods in their diet. Since the 1950s, Australia has destroyed at least a quarter of its saltmarshes; in some estuaries, it's as high as 80 per cent. Rising sea levels will inundate more.

Jock hopes we can help protect what's left. Our task is to assess the condition of the saltmarsh and consider any threats it might face, then score these on a sheet. The saltmarsh could be disconnected from the sea by a road or drain that blocks fish from following the tide in. There could be pollution from a nearby factory, or nutrient run off from homes. They might even be mowed (but not these ones).

It's subjective, and is designed to determine the issues most important to the community doing the citizen science.

My favourite part of the exercise was the chance to slow down and spend time being attentive to a place I knew nothing about and had ignored. Many of us expressed wonder in this unlikely place, with is gradual reveal of birds, spiders, crabs, sedges, rushes, reeds, herbs and shrubs, it's colours and subtle connections.

'You don't know what's right under your nose,' remarked Lisa, a Gladstone local.

As we continue in a time of rapid ecological disruption, the places we don't consider scenic or beautiful, the places we'd prefer to disregard or turn away from, might be the places most in need of attention and care.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.